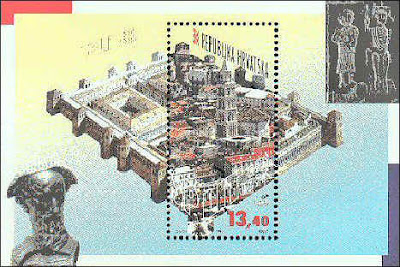

While I was looking for Georg Niemann's images of Split ca. 1907 I happened across a reference to Robert Wood's

The Ruins of Palmyra, otherwise Tadmor, in the desert (London, 1753), and it actually made me sit up and clap my hands, because Palmyra is one of my favorite places, and to find such a plethora of wonderful images is like getting the best kind of birthday presents.

I went to Palmyra in the early 1990's, before Americans were

persona non grata in the Middle East (yes, that recently. We were actually welcome a lot of places back then). I went on a 5-week trip with my good friend Gwyan, who was working in London with me doing graphics at the time, to Turkey, Syria, Jordan and Israel. It was a fabulous trip, and one of the best places was the long-lost desert city of Palmyra, destroyed as an example by a Roman emperor.

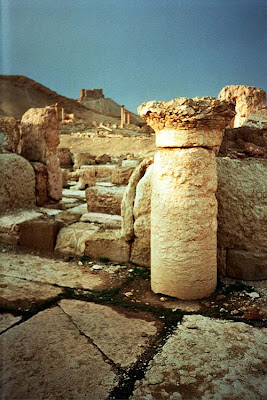

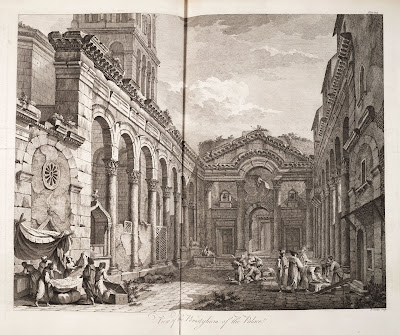

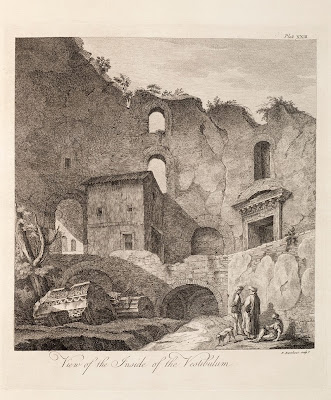

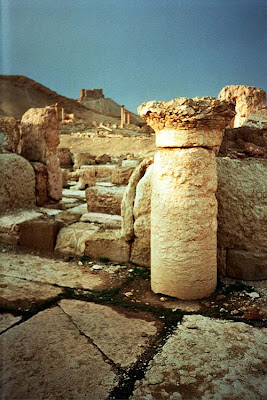

We went from by bus from Hamma before going on to Damascus. I remember seeing a many-pointered sign-post on the way of which one of the pointers (pointing off into sandy flatness) said, "Baghdad 413 km" (or something), and feeling completely surreal. When we got there, we were blown away: across the desert, scattered around like toothpicks after a storm, were hundreds of beautiful sandstone columns, statues, carved cornices, and so on - carved from a beautiful orangey stone, like the desert itself. Some of it still stood (or stood again), some of it lay flat, and some was piled up randomly like pick-up sticks.

Nearby was a podunk little town of cement-block housing and boiling-hot, straight, lonely streets crammed up against high earthen walls. Within these walls lay the delicate heaven of the oasis itself: acre after acre of green trees and bushes, surrounded by ditches and pools of water, soaking into the fine desert soil. Where the wall grew lower we would linger, staring at the bounty and the lushness, and wish we could go inside.

The town was full of bored Arabs and on the outskirts, and in the ruins themselves, one could see Beduin folk hanging out, making tea or riding their camels or horses in lovely dark blue robes, the horses or camels arrayed in hand-woven saddlecloths with long tasseled bits. It was almost shockingly romantic.

Several of the buildings in the town housed trinket stores and sold things such as Beduin cloth, souvenirs, postcards of the Godforsaken main street, and any number of other things. I had always wanted a Beduin camel-blanket and found one in a little store run by a young man who looked as if he were about fifteen. After seeing the ruins we went in and bargained with him in a desultory way, drinking cups of sweet tea and discussing the price in a very slow and roundabout flirtation between buyer and seller. After awhile, he heard we were glassblowers and offered to show us his secret room. But more about that below.

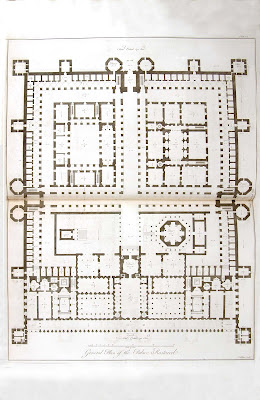

Palmyra itself began as an oasis town:

"...[it] was made part of the Roman province of Syria during the reign of Tiberius (14–37). It steadily grew in importance as a trade route linking Persia, India, China, and the Roman empire. In 129, Hadrian visited the city and was so enthralled by it that he proclaimed it a free city and renamed it Palmyra Hadriana." [

wiki]

The city is cited in a number of texts (under the name of

Tadmor) as having been built by King Solomon, and with Roman conquest grew to be an extremely prosperous and elegant city, with a key part to play in the importation of desirables from the East to the Roman empire.

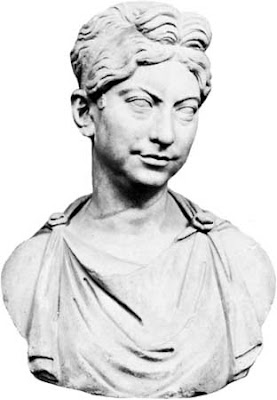

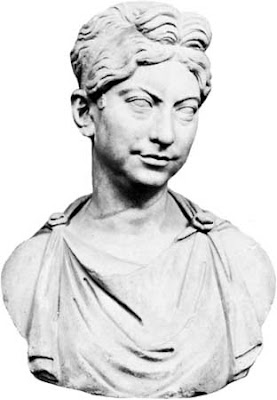

"Beginning in 212, Palmyra's trade diminished as the Sassanids occupied the mouth of the Tigris and the Euphrates. Septimius Odaenathus, a Prince of Palmyra, was appointed by Valerian as the governor of the province of Syria. After Valerian was captured by the Sassanids and died in captivity in Bishapur, Odaenathus campaigned as far as Ctesiphon (near modern-day Baghdad) for revenge, invading the city twice. When Odaenathus was assassinated by his nephew Maconius, his wife Septimia

Zenobia took power, ruling Palmyra on the behalf of her son, Vabalathus. Zenobia rebelled against Roman authority with the help of Cassius Dionysius Longinus and took over Bosra and lands as far to the west as Egypt, establishing the short-lived Palmyrene Empire. Next, she attempted to take Antioch to the north. In 272, the Roman Emperor Aurelian finally retaliated and captured her and brought her back to Rome." [

wiki]

Zenobia, known as "the Warrior Queen", expanded her empire and took over Egypt at the age of twenty-nine with her mounted desert-tribe soldiers and a great deal of skill, but was doomed to lose it within a

very few years:

"In her short lived empire, Zenobia took the vital trade routes in these areas from the Romans. Roman Emperor Aurelian, who was at that time campaigning with his forces in the Gallic Empire, probably did recognise the authority of Zenobia and Vaballathus. However this relationship began to degenerate when Aurelian began a military campaign to reunite the Roman Empire in 272-273. Aurelian and his forces left the Gallic Empire and arrived in Syria. The forces of Aurelian and Zenobia met and fought near Antioch. After a crushing defeat, the remaining Palmyrenes briefly fled into Antioch and into Emesa.

Zenobia was unable to remove her treasury at Emesa before Aurelian successfully entered and besieged Emesa. Zenobia and her son escaped from Emesa on camel back with help from the Sassanids, but they were captured on the Euphrates River by Aurelian’s horsemen. Zenobia’s short lived Egyptian kingdom and the Palmyrene Empire had ended. The remaining Palmyrenes who refused to surrender were captured by Aurelian and were executed on Aurelian’s orders."

Except for Zenobia: she was taken back to Rome and paraded through the streets in golden chains. Aurelian was so impressed with her beauty, dignity, intelligence and general queenly bearing, however, that he pardoned her quickly and gave her a villa in Tibur (now Tivoli) where she lived in luxury, becoming a respected socialite, prominent philosopher and wife of a Roman governor and senator - and bearing the ancestors of many prominent Roman citizens.

I think this is one of the most interesting stories I know about this time period. And the ruins themselves live up to it, that's the best part. The rug dealer's secret room, however, did not.

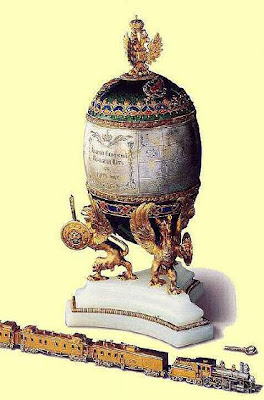

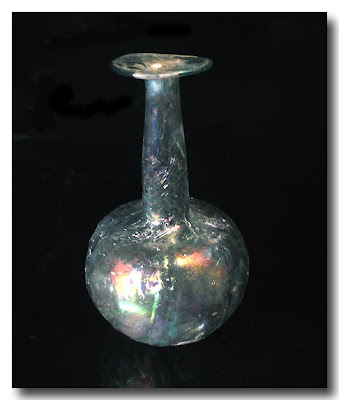

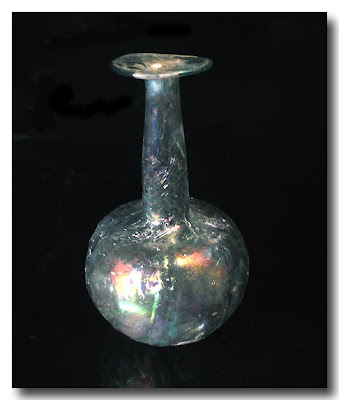

It was a tiny room with florescent lighting. All along one wall were shelves and shelves of ancient Roman artifacts - small ones, such as coins and dusty, devitrified little bottles and shards of Roman pottery. "Glass," he told us, gesturing, "Roman glass."

Not my fake: this is what it's supposed to look like!

We looked at the glass with the practiced eye of glass people, and shook our heads, smiling. "This isn't old," we said. "Come on, admit it!" We said this with smiles and the sort of gentle nod-and-wink conspiratorial air of people who had been drinking tea with another person for two days. "No, no, really," he protested, his hands held out palms up, "Roman glass!"

We began to point out all the ways the glass didn't really look like truly aged glass. The oily sheen, we said, that was supposed to be age, wasn't on the surface of the glass, it was somewhere...inside it. We weren't sure how, but it seemed awfully like Mylar stuffed down inside.

He began to grin - he just couldn't help it. He was only fifteen, after all. Picking up one bottle, he showed it to us: "This one, made of a light bulb, cut off on the bottom. The neck - only plastic! See? Easy to melt so the top looks like it's hand-made."

We peered at the thing closely. Covered with a layer of sprayed-on grit, there was a little window for the Mylar to peek out, and the neck really was plastic! We started laughing, and couldn't stop. It was hilarious! A light bulb! Cut off! He showed us some of his other things, and described how it was done. In the end, we bought the light bulb one from him, along with some other ones that we thought were wonderfully inventive - AND the Beduin camel-blanket - and shook hands with him, thanking him for making our trip so much more interesting.

So who was laughing all the way to the bank? Who cares? I still have the light bulb bottle, and it still makes me smile. More, perhaps, than my beautiful pictures of the fabled city of Palmyra.

(The two modern images of the ruins are from an

unknown website with beautiful travel photos)